A Bobolink’s Carbon Fingerprint

Note: This is my latest column from Northern Woodlands magazine.

LIFE CAN BE ROUGH FOR A BOBOLINK, a charismatic grassland bird whose population is declining. And halting that decline is a challenge for North American ornithologists. After all, Bobolinks spend about eight months of the year, from September through April, either in long-distance migration or at wintering sites in South America.

But the ornithologists don’t necessarily need to chase these songbirds across the Llanos or Pampas. It turns out that when Bobolinks return north each spring, they unwittingly bring back clues about what they were up to during winter.

The evidence is encrypted in their feathers.

To understand what feathers can reveal about bird behavior, I offer you a short refresher course in nuclear chemistry. (Stay with me; this is cool stuff.) Recall that an element’s nucleus contains, among other crazy particles, protons and neutrons. The most abundant form of carbon, Carbon 12, for example, has six protons and six neutrons.

But nuclei sometimes contain extra or fewer neutrons. These are isotopes, some of which are unstable or radioactive. But others persist in the environment – and in feathers. One of these stable isotopes is Carbon 13. Although it’s scarce, Carbon 13 in feathers can tell us a lot about what Bobolinks were doing in South America last winter.

So where might a Bobolink pick up its carbon? The only source is food – insects and seeds from wild, native grasses. But Bobolinks also feed on cultivated rice in South America. That’s a problem because rice farmers sometimes use organophosphate pesticides, including one called monocrotophos, which is notoriously toxic to birds.

The carbon in feathers can reveal what a Bobolink was eating. Rice has a particular carbon signature, based on the relative abundance of Carbon 13 and Carbon 12 (from carbon dioxide) that the plant assimilates during photosynthesis. Rice has a higher proportion of Carbon 13 than native grasses, and this carbon isotopic ratio is like a tracer, moving from carbon dioxide in the air to rice to feather. Basically, you are what you eat. And that distinctive carbon ratio, like a fingerprint, stays with a bobolink when it returns north to breed in May.

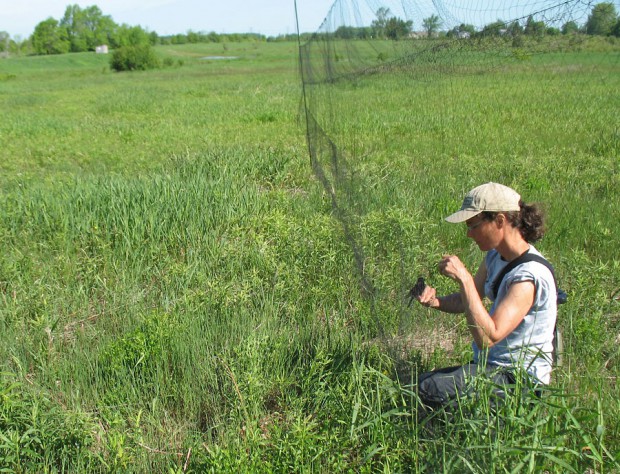

Here, waiting for Bobolinks, is my colleague Rosalind Renfrew, a conservation biologist at the Vermont Center for Ecostudies (VCE). By clipping off and analyzing the tips of a few wing feathers, Roz can determine whether a particular Bobolink has been feeding on rice or on wild grasses. She can then investigate whether this hampers a Bobolink while nesting and fledging young here in the U.S. or Canada.

But there’s something unusual about Bobolink biology that makes this research even more powerful: Bobolinks grow feathers like few other birds. Nearly every species of North American migratory songbird molts its wing and tail feathers only once a year, usually after breeding. Those new feathers give songbirds greater efficiency during their long flights south. But Bobolinks grow an entirely new set of wing and tail feathers during the winter as well. Very few birds do this. During earlier trips to Bolivia and Argentina, Roz figured out the timing and orderly sequence of the Bobolink’s winter molt, which generally runs from mid-January to early March.

Each new feather, grown at a particular time during the molt period, takes on the carbon fingerprint from whatever the Bobolink happened to be eating at the time. Each feather is like an entry in a diary that the Bobolink carries north. So when Renfrew clips a particular feather she can determine not only what the Bobolink was eating (rice or native grains), but when during its molt cycle it might have been facing risk in rice fields.

Renfrew has concluded that some Bobolinks eat rice for most of the winter, some eat native grasses instead, but most of the birds go back and forth on their diets. Bobolinks do seem to hit the rice in April on the way north.

Renfrew has plenty more to do on behalf of Bobolinks, including working with rice farmers to curb pesticide use. For that work, an extra neutron in Carbon won’t do her any good: Renfrew will need to book a flight to South America.

Thanks, Willem. Check me on the chemistry!

Very interesting subject, and very well described. You’re a born teacher, Brian!

Thanks, Ginny. VCE has a lot of great work happening on Bobolinks. Here’s more:

http://vtecostudies.org/projects/grasslands/bobolink-research-and-conservation/

Best,

Bryan

Bryan,

So grateful for the work that you, Rosalind, and others are doing to better help the beautiful Bobolink. Years ago they were a common site in the farmlands of central NY and in the Tug Hill region as well. Now I’m lucky if I see a couple now and then. Makes me so sad. Hopefully, the work you are all doing will help to restore their numbers. Good luck and thank you.

Ginny Alfano

Cleveland, NY

Guilty as charged, Marcia!

Ah, I knew you were a chem major way back when! Very interesting!

Thanks, John. Also check out the cool grasslands work at VCE:

http://vtecostudies.org/projects/grasslands/

GREAT post! Many thanks. Also, all of us can help preserve essential farm fields here in New England by participating in the Bobolink Project (http://www.bobolinkproject.com/index.php) which pays farmers to delay cutting hayfields until the birds have nested and fledged. Thanks Bryan.