Cheating Death

A Moth, a Carnivorous Plant, and a Barbara Kingsolver Novel

The specialized leaf of a pitcher plant is a cunning chamber of death. Its purple and crimson hues beckon insects with a deceptive promise of nectar or flesh. Once it takes the bait and enters the chamber, the insect is doomed. Death comes by drowning. The prey dissolves in a toxic pool of enzymes and bacteria. The plant appropriates the remains.

That is unless the insect cheats death like a Pitcher Plant Mining Moth (Exyra semicrocea).

Yellow and black, and about the size of your fingernail, this moth comes and goes about the pitcher plant as it pleases, using the death chamber as its crash pad. And if that isn’t audacious enough, the moth lays a single egg on the inside of the pitcher wall. A caterpillar hatches and proceeds to eat the chamber. A carnivore falls to an herbivore.

Yellow and black, and about the size of your fingernail, this moth comes and goes about the pitcher plant as it pleases, using the death chamber as its crash pad. And if that isn’t audacious enough, the moth lays a single egg on the inside of the pitcher wall. A caterpillar hatches and proceeds to eat the chamber. A carnivore falls to an herbivore.

I’ve met this moth only twice — first in a coastal wet prairie on the Florida Panhandle this past spring and again on the cover of Barbara Kingsolver’s latest novel Unsheltered, which I have just finished. As usual, Kingsolver is brilliant. But the book’s cover art, rendered more than a century ago by the English naturalist and painter John Abbot (1751-c.1840), launched me on a second adventure, an odyssey of natural history and mistaken identity.

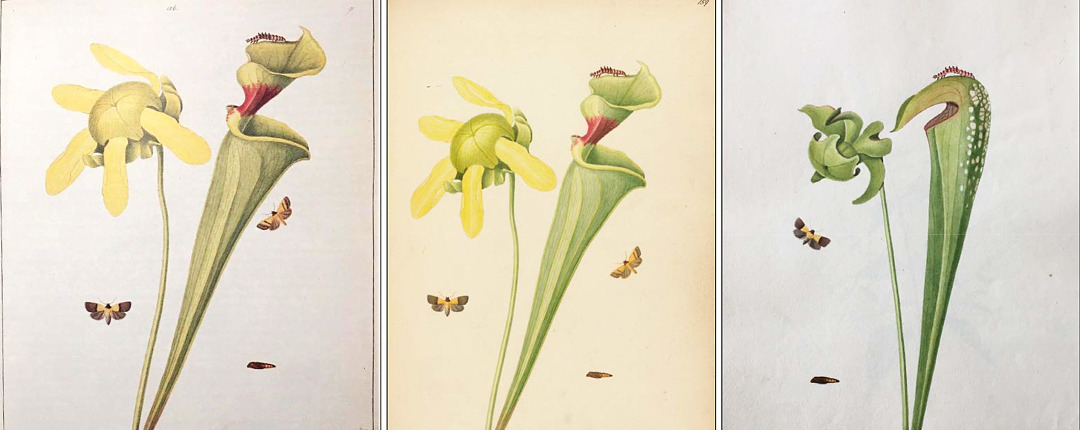

From the comfort of my favorite reading chair, the cover transported me back to that prairie in Florida and then onward to the Natural History Museum in London, where Abbot’s painting resides, and finally to consultation with a corps of my colleagues in entomology and botany. I now return to report that both of the moths in Abbot’s painting (and on Kingsolver’s book cover) have been misidentified. Even so, here at the start of a new decade, during a harsh and perilous time for our politics and planet, these daring insects might offer us a bit of hope on the wing.

[] [] []

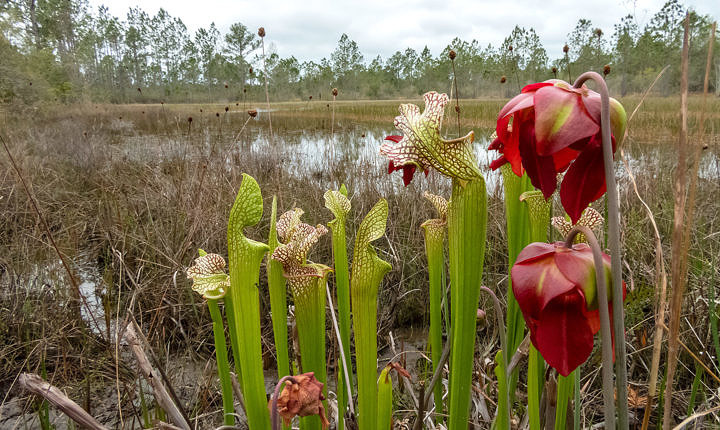

The banner photo above is my point of origin, the wet prairie at Yellow River Marsh State Park outside of Pensacola, Florida, on March 31, which was a lousy morning for dragonflies. No matter. Steven Daniel, Josh Lincoln, Laura Gaudette (In the photo) and I had other things to discover on the prairie, including the Yellow Pitcher Plant (Sarracenia flava) of Kingsolver’s book cover. But we also found in abundance the Siren of these wetlands, the globally vulnerable White Pitcher Plant (Sarracenia leucophylla).

Tall, slender and fetching, White Pitcher Plant towers over its relatives. I would sooner than the moth crawl into its chamber. Instead, when I find these plants I routinely peer into their pitchers, where I usually find a porridge of carnage. So consider my shock (and awe) in the prairie when I found live moths looking back up at me. Laura had already noticed them, knew of them, and was busy taking photos. Here below is a montage (click any for more complete views) of plant and moth.

Not long after returning home from that expedition to the Southeast, I discovered the Kingsolver novel and its cover with Abbot’s illustration of Yellow Pitcher Plant (Sarracenia flava), easily identifiable, along with a caterpillar and two moths in flight (find the full image below).

The moth flying lower left seems to match the moths we saw on the wet prairie: Pitcher Plant Mining Moth. Same goes for the spiky caterpillar — at least a member of that moth genus — Abbot depicted crawling atop the Yellow Pitcher Plant. But what about that other adult moth to the right of the plant? I wasn’t sure. So I hunted down online notes that trail this painting around the web. The notes misidentify both moths: as Half-yellow Moth (Ponometia semiflava) on the left and Ernestine’s Moth (Phytometra ernestinana) on the right.

A version of Abbot’s painting once owned by American botanist Asa Gray, who annotated the illustration with “Sarracenia flava” (Yellow Pitcher Plant). Credit: MS Typ 426.2. Houghton Library, Harvard College Library

At this point I reached out by email to a talented corps of biologists, most importantly the lepidopterist John V. Calhoun. A research associate at the McGuire Center for Lepidoptera and Biodiversity, in Gainesville, Florida (my destination next week), and an Abbot scholar, John has a particular fondness for early lepidopterists and for solving taxonomic discrepancies owing to missing or overlooked type specimens. Not only that, he’s been a colleague and mentor in some of my butterfly expeditions for the State of Maine. Having published extensively on Abbot, there is no better authority for this adventure than John Calhoun. And he delivered.

John pointed out that the Kingsolver cover image is from a series of Abbot’s illustrations, now in large part housed at the Natural History Museum in London, rendered sometime around 1800-1810 while Abbot lived in Burke County and Savannah, Georgia. It is among a 17-volume collection of Abbot’s work once owned by John Francillon, a London jeweler, naturalist and an agent for sales of the artist’s illustrations and specimens. Abbot had included notes for each drawing, which Francillon transcribed but then discarded. The notes for this particular illustration (as transcribed by Francillon) read in part (with John’s explanations in brackets):

“The caterpillar feeds on the trumpet leaf. It spun up [pupated] in the leaf in the hollow part 12th June. Bred [emerged as imago] 24th. The Moth may also be found sometime in the hollow of the leaf and it flies in the evening. It is Rare. Many insects of different classes creep into the hollow of the leaves for shelter where they drowned by rains filling the hollow of the leaf, as they are unable to get out again from the wet and the shape of the leaf….”

John noted that the misidentifications could not have been Abbot’s fault. One of the two species wasn’t described to science until the listed year of Abbot’s death (1840) and the other 12 years later. Even so, Abbot’s portrayals weren’t always entirely accurate. He sometimes associated insect species with the wrong plant hosts, placed adults with their wrong early life stages, or failed to render certain details, all of which made some of his illustrations — especially small moths — difficult to identify with certainty. So the misidentifications likely came later by someone at the museum in London. (For much more on Abbot and his illustrations from Georgia, consult John’s amazing and comprehensive paper, two decades in the making, recently published in the Journal of the Lepidopterists Society [Calhoun, 2019].)

Abbot probably did believe the two moths to be male and female of the same species. We now know better. The moth on the right (although hard to ID) is almost certainly Riding’s Pitcher Plant Looper Moth (Exyra ridingsii), whose life cycle plays out in Yellow Pitcher Plants in bogs, pine savannas and pocosins of the southeastern U.S. (Ricci, 2017). The moth on the left is indeed, as I had suspected, Pitcher Plant Mining Moth, the very same species we encountered in the those White Pitcher Plants on the wet prairie in Florida.

Maybe these moths, unsheltered and on the wing, can represent a bit of hope for the planet in 2020.

As for Kingsolver’s novel, as it turns out, neither the moths nor pitcher plants figure in the plot, although the botanist Mary Treat (1830-1923) is a force of nature in the book, as she was in life, notably for her studies of carnivorous plants. A colleague of Treat’s, Asa Gray (1810-1888), among the most esteemed of American botanists, who once owned a version of the Abbot illustration, is the only other character in common with the novel and Abbot’s illustration. (Well, so is Charles Darwin, who is, after all, a common intellectual ancestor to every thinking person.)

The moths are not named in Unsheltered‘s cover image credit. So no harm done to the novel. But perhaps Kingsolver missed a literary opportunity, which I myself shall now claim here in the Anthropocene and at the start of an election year in the U.S. (Fear not — no plot spoilers ahead.)

Unsheltered follows the lives of two families who shared the same crumbling home in Vineland, New Jersey, about 150 years apart — one contemporary and the other in the 1870s in the wake of Darwin’s publishing On the Origin of Species. I need not reveal much else about the plot other than to say Kingsolver navigates, along braided paths, the inconvenient truths of Darwin’s theory (now law) of evolution, creationism, the climate crisis, family, and the Trump presidency. Amid world views in flux, and now a world itself in peril, in the fog of ignorance, and in the face of horrible injustice, Kingsolver illuminates (especially for we boomers) our turbulent past and our shared, perilous fate. She reminds us of solace we might find in nature. And perhaps even hope in wild places and human spirit.

But maybe these moths can offer us something else. Recall that the pitcher plant lures its insect prey into the death chamber with a lie — the guise of a flower or the fake reward of flesh. Not that I begrudge the plant for its adaptation. Deception is the legitimate way of nature. It has become the illegitimate way of our politics.

But the moths defy mendacity, they cheat fate in the death chamber, even thrive in it. Then they fly free — unsheltered, even in darkness, seeking the light. I’ll take that as a kind of hope for 2020.

To my readers, and for our planet, its people, wildlife and wild places, I wish a peaceful new year.

References

Calhoun, John. 2019. From Oak Woods and Swamps: the Butterflies Recorded in Georgia by John Abbot (1751-c.1840) Based on His Drawings and Specimens. Journal of the Lepidopterists’ Society. 73. 211-256.

Jones, Frank Morton. 1921. Pitcher Plants and their Moths. Natural History, Vol. XXI, No. 3. 296-316.

Ricci, Christine & Meier, Albert & Meier, Ouida & Philips, T. 2017. Effects of Exyra ridingsii (Lepidoptera: Noctuidae) on Sarracenia flava (Nepenthales: Sarraceniaceae). Environmental Entomology. 46. 10.1093/ee/nvx171.

John Abbot and William Swainson: Art, Science, and Commerce in Nineteenth-Century Natural History Illustration by Janice Neri, Tara Nummedal, and John V. Calhoun. University of Alabama Press.

Acknowledgments

In addition to the intrinsic joy of this literary and natural history adventure, I’m grateful for my three compatriots in the prairie: Steven Daniel, Josh Lincoln, and Laura Gaudette. But along the way I reached out to two additional friends in entomology, JoAnne Russo and Hugh McGuinness, as well as another John Abbott, this one still living (but with an extra “t” in his name), a colleague in Odonata who recently described a new dragonfly species — Sarracenia Spiketail (Cordulegaster sarracenia) — from pitcher plant wetlands in the Southeast (see my image below). Laura, JoAnne, Josh and James Adams independently confirmed identifications of the two moth species (There’s a nice symmetry to James, a noted Georgia lepidopterist, contributing an ID to one of Abbot’s illustrations from their shared state.) And John V. Calhoun has been indispensable on Abbot and for his wisdom on some of Maine’s most wonderful butterflies.

Oops, my comment about Louis Megyesi posted, I think, in the wrong place. Sorry.

Hi,

Are you Louis Megyesi, the artist? I recently purchased a watercolor print by an artist of that name. It’s a beautiful watercolor print of The Red House in Maine.

That means a lot to me, Dru! Thanks. Best for 2020 to you and Don!

Thanks, Marie!

Fabulous! Thank you, Bryan.

Thanks, Bryan. What a great read.

Thanks, Scott. I haven’t read that one, but I’ll certainly check it out. My FOY is also AMCRO! But a Carolina Wren called from near the house this morning. Not a bad start! And regards to Pat!

Very kind of you, Willem. Some cool chemistry in those pitchers, no? 🙂

Thanks, Sarah! Let’s meet up in FL!

Well, if I helped end your year on a perfect note, thanks for striking all the right chords for me in 2019! 🙂

Great piece, Bryan. Pat is reading the Kingsolver book at present. I’ll pass this along — I’m sure it will make the read all the more interesting.

Did you happen to have a chance to read Darwin’s First Theory: Exploring Darwin’s Quest for a Theory of Earth by Rob Wesson. Chip and I enjoyed it.

Happy New Year and Good Journeys

Scott

First bird of the year — a family of crows chasing a Red-tail across the fields of our farm.

You’re the epitome of a writer-scientist, a top practitioner in both worlds. Also, with your intriguing description of Kingsolver’s novel, I will suggest it as a candidate for my book group.

Your prose gets better and better, Bryan. I relish each chapter!

About to head south to the FL panhandle where we rent on Cape San Blas with my sister and family for two months.

Check out the author website for my new novel Landing, linked below, which contains lots of lovely botanical descriptions.

Wonderful story-telling science, as usual, Bryan—thank you for helping me end the year on a perfect note!

Thanks, Brian. (I will confess to looking up “perspicacious” — so thanks for that as well!) 🙂

Wow back atcha. Hope to see you in OK next summer!

So kind of you, Yvonne. Thanks so much. You’ve captured it all as well. Perhaps I’ll see you around the city again! Happy New Year.

Thanks, Lisa. Here’s to hoping you that look keep looking and keep finding other things as well!

Hi, Louis and Beverly. Thanks so much for the kind words. Oh, how I could have written on longer about life and death in that pitcher. But the new year was fast approaching. 🙂 Best to you in 2020 and beyond!

Lovely, thought-provoking, and perspicacious, as usual. Thanks, Bryan.

just WOW!

Brian, I always loved your incredible writing! Thank you for a thought provoking, interesting piece. I like the comparison you make in the end, “lie and deception” and then “cheating death” or demise in the death chamber… and then “thriving” through all this, plus leaving a death and life signature in the plant… and so yes, there is hope in the end… it can be compared to politics as you suggested in a smooth way… and there will always be winners and losers. Nature and life are a real mystery! Thank you for your wonderful thoughts! Hope 2020 will be better for all of us. Wish you well.

Thank you for this, Bryan… now I have a couple more books to add to my to-read list. And I love the stories that come out of “I was in the field looking for one thing, but found another thing instead….”

See you in the field in 2020!

Bryan, once again you inspire Beverly and me to stop a little longer to admire the beautiful intricacies of nature. Your article and photographs were fascinating. Who knew there was such a fantastic world inside of a pitcher plant? Bryan Pfeiffer thought there might be, and so he stopped to take a closer look and found it there. Thank you for helping us enjoy the world around us.

This is so kind of you, Ginny. Thanks. It means a lot to me. You’ve made my day.

Kingsolver is a gift, as are those pitcher plants and their inhabitants.

… and best wishes in return for your adventures as well, Dan. We’ll sort of cross paths. I’ll be at Paynes Prairie and Sweetwater soon!

Thanks, Kapez! Great to hear from you.

Thanks, Ann. I could have written twice as much about life and death in that wet prairie. (Perhaps I will.)

Thanks, pal! Same to you and Anne — and no health adventures in 2020!

You must illustrate those luscious crimson and white pitcher plants! 🙂

Thanks, Veer. I enjoyed the Overstory. Such a different novel, as I’m sure you know. It’s magisterial; Kingsolver is, well, more grounded (literally and figuratively) by comparison. The Overstory often made me gasp; Unsheltered made me think. 🙂

I’m grateful for your kindness, Carolyn. My book is in the works! 🙂

Thanks, Roger. I’m glad we got to share some of this last April!

Once again, Bryan, you wrote a fascinating, thought provoking, thoroughly researched article on a tiny creature, its host plant and an incorrect identification that most people would never have thought or cared about. That is, until you wrote about it. Now, you have filled my mind with visions of little caterpillars, moths and pitcher plants the likes of which I never knew existed. Your uncanny ability to make things live in both photos and words is something I’m amazed by and so look forward to every time an email from you appears in my “inbox”. Thank you for brightening up an otherwise dreary winter day! Now I’m off to buy a book………….

Thank you, Bryan for transporting me back to Florida. I returned home to New England from Gainseville in time to deal with our recent mush of snow and ice – I so enjoyed Sweetwater Wetlands Park and Payne’s Prairie – need to set my sights now on Florida’s panhandle next trip south! So enjoyed reading this post … as I do all of your posts! Best wishes for wonderful adventures in 2020! Dan

Very nice way to pull us out of our day to lives, into the field, meadows and bogs. I think I’m there.

Great story and mental image Lemont. From Kapez.

What fascinating and beautiful moths, with such incredible adaptations. Thank you for a really educational post. Must get that new Kingsolver book!

Wonderful yarn from a detective philosopher naturalist. Keep them coming.

Good health for the new year

Hah! Are you getting a slice of book sales? You should because I, too, will have to run out and get it! Thanks for not only the botanical history lesson Bryan but that little seed of hope. Happy New Year to you!

This post = erudition + charm of observation, x real-world nexus of politics and nature. Plus photos of mysterious life forms! Cannot help getting reverberations of Pynchon’s Vineland, and the recent, and astonishing, R Powers’s The Overstory. Thank you, Bryan, for pointer to the new Kingsolver, and this view of things that you offer.

Now I need to read the book! Maybe one day you’ll write one too. You are an incredibly engaging writer! Can hear your voice as I read your blog – Happy New Year!

Carolyn

What a wonderful synthesis of disparate information! Thanks, Bryan