Refuge in a Flower and its Bee

Prologue: Longtime readers may know of my fondness for Fen Grass-of-Parnassus (Parnassia glauca). Every year I seem to discover something new about this elegant plant: its rare bee, for example, or its pollination antics. During casual research this year, I’ve been finding more than beauty and the bee. It is the subject of my latest essay for The Boston Globe, presented for you here.

As a research subject, object of beauty, and master of deception, it may be hard to beat Fen Grass-of-Parnassus.

Not a grass, this perennial plant features a rosette of leaves at its base from which an elegant stalk rises to display one of the loveliest and most duplicitous blooms of late summer.

The flower’s symmetry, with five pearly petals marked with sharp green stripes, and its alluring reproductive parts bring me literally to my knees. Day after day, regardless of rain or mosquitoes or my mood, I have been crawling around in order to study how Fen Grass-of-Parnassus, um, well, you know . . . gets it on.

Along the way, I’ve made two important observations. First, in this drama of reproduction, the plants at my study sites here in Vermont cavort with a bee found nowhere else but in the company of Fen Grass-of-Parnassus. More important, in my own cavorting with Fen Grass-of-Parnassus, my modest study has become a kind of meditation on beauty and the unruly pace of life.

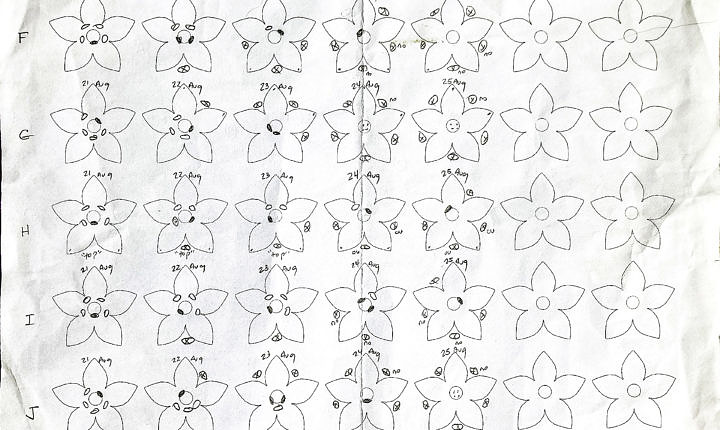

A “Day-2” flower. Yesterday’s stamen, at 12-o’clock, has completed its mission and moved out of the way. Today’s stamen, at about 2-o’clock, has elongated and bent its brown anther over the pistil. Three more stamens clustered around the pistil have yet to make the maneuver. A bee has already taken the day’s pollen, leaving a bit on two of the undeveloped anthers. (Those 15 fake nectar drops are actually five tridents.) Click for a bigger view.

Curiosity drove me to these plants. I wanted to understand the lengths to which the flower’s male parts, its five stamens, go to offer pollen to that rare bee, whose given name is Parnassia Miner. What I’ve been finding so far is that on most days only one of the five stamens participates in the mating game. It lengthens and positions itself so that the bee picks up pollen and then flies off to unwittingly deposit some of it on the female part, the pistil, of another flower. After its single day in the limelight, the stamen retracts and another takes its place.

To get the most benefit from this one-stamen-per-day antic, the flower also employs subterfuge. It stations 15 yellow beads, resembling drops of nectar, to entice and orient the bee just right to foster the exchange of pollen from plant to plant. But those droplets, like shiny glass candy, are fakes. I have watched various ants, flies, and the bee in particular appear to fall for this ruse. (Genuine nectar is probably located at the base of these structures, called “staminodes.”)

In my more than 100 flower observations, I have also discovered that these stamen gyrations aren’t as predictable or orderly as I had expected. They proceed in no fixed order, for example, and sometimes two stamens per day make the pollination maneuver. So, like romance in general, it’s complicated. And that’s fine.

Like romance in general, it’s complicated.

By no means a botanist, I am driven by exuberant curiosity and inordinate beauty. During my daily visits with my study flowers, I have come to know their unique folds and flaws and tendencies. Each bloom is not merely a pretty thing but rather an ongoing story with a plot line and four major characters: the stamens, the pistil, the fake nectar, and the bee.

And in these flowery dramas I have discovered something else, something unexpected: respite. When I visit with Fen Grass-of-Parnassus there is no email inbox, no culture wars, no news from Ukraine, no routine daily worries or annoyances. Among these blooms I do not even turn my gaze toward other charismatic nature nearby: warblers calling overhead, for example, or intricate white orchids blooming at one of my study sites.

“To be everywhere at once is to be nowhere forever, if you ask me,” Edward Abbey wrote in his essay “Walking.”

If you ask me, to be alone with Fen Grass-of-Parnassus is to be blissfully nowhere else. A single flower is refuge from the daily fusillade of distraction. Nature is good for that. Like sex or chocolate, like the Bach cello suites or love for another person, a flower can be a genuine manifestation of joy and wonder and mystery.

Then again, sometimes a flower is just a flower — simply and objectively and forever beautiful.

Acknowledgments, Notes, and References

- Besides the flower itself, inspiration for this humble field project comes from the fine work of W. Scott Armbruster and colleagues, who published on another Parnassia species. Max McCarthy as well is doing groundbreaking work on Parnassia Miner and its favorite plant. Scott and Max kindly replied to a few of my questions about these plants and their bee.

- The middle flower in this post’s banner image has completed its five stamen gyrations. Only then (and never before in any of my study plants) does the pistil’s white stigma (dead center) emerge. It is a protection against self-pollination.

- My friend and colleague Steven Daniel first alerted me to this once-a-day (more or less) stamen maneuver — among my many gifts from this exquisitely talented botanist and all-around naturalist. The incredible field naturalist and botanist Grace Glynn and I began these stamen observations last year.

- Tracy Sherbrooke here in Vermont also watched Fen Grass-of-Parnassus flowers and pollinators day after day this year, recording data as well. Her results appear similar to mine. Thanks so much, Tracy!

- Those flower images with black backgrounds, indeed field shots, result from camera settings: a stopped down lens (usually f22 or f24) and front-of-the-lens lighting (Canon Twin-Lite on my 100mm macro lens). It also helps that Parnassia glauca‘s flower extends alone above the basal leaves by up to a foot or so. Each shot received standard PhotoShopping.

- Noteworthy research from China on sequential stamen movement and efficiency of pollen transfer.

- With some relevance to my findings, additional research from China on one-stamen-per-day and anther-anther interference.

- Finally, I’m also most grateful for Bragg Farm Sugarhouse & Gift Shop in East Montpelier, Vermont, whose maple creamees were welcome treats on my way home from field sites.

More Images

What I call a Day-0 flower. None of the stamen's filaments has elongated; the five anthers remain undehisced and tight around the pistil (not yet showing its stigma).

All five stamens, having completed their maneuvers, have retracted out of the way of the pistil, which now shows its four-parted stigma dead-center.

Previous Related Posts

A Flower's Gyrations

Last year's more detailed explanation of sequential stamen movement, which got me thinking about questions for this year's work.

A Rare Bee and Audacious Beetle

Along with the bee, I bring you a beetle that, when swallowed by a frog, proceeds to crawl out of the frog's butt unscathed.

Thanks, Dennis. I heartily agree. And I wish we had Parnassia fimbriata growing here! Those lacy petals and odd staminodes are really something. I hope to see that flower before I leave this earth!

Bryan, that’s lovely. You can’t go wrong by sitting and watching a flower. I wish that species grew in the Pacific Northwest, but we have Parnassia fimbriata instead, which presumably has a reproductive strategy of its own, yet to be revealed.

I think that’s correct — it seems that they don’t mind disturbance, and we’ll have to do some research about how they “move.” Looking forward to it!

Thanks so much, Tracy. I’ll bet we’ll be back next year with more questions and wonderful mysteries to solve.

P.S. My “jump the road” comment has me wondering how they propagate to new locations…I note that they do not object to some disturbances or even mowing. Our neighbor – early in May – mowed a verge near our home that has not previously had many FGoP – and these lovely little flowers were absolutely prolific in that area come August.

This article is beautiful, Bryan. And I wholeheartedly agree in the lovely act of getting lost in the beauty of this plant. Thanks for including me in your project – so much. I was thrilled to discover some this morning on my walk with my daughter’s pup that are still in tight bud phase – and some that have “jumped the road” in one spot – a little patch where none had been before. Filled with such promise!

Bryan, very interesting observations of this unique flower! Fantastic photo work that clearly show your findings.

How widespread is this particular bee in Vermont? Are there other flowers found in Vermont that use similar reproductive strategies?

Fernando

You mean, “Get a photo that’s in focus next time.”!

Thanks, Ann. Get a photo next time! 🙂

Other pollinators do indeed visit these flowers, including other bee species. Still so much to learn about all of them. Thanks, Melinde.

Thanks, Susan. Yeah, those pinstripes really help make this flower so compelling.

Yeah, “fenny” places — but not always. It’s odd. Check iNaturalist for sites. (They’re going by now — but still some in bloom.)

Nice to hear from you, Cindy. Hope you get on the road again!

Wish I had used “choreography!”

Very kind of you, Georgeann. Check iNaturalist for sites!

We need more singular foci (or, er, focuses), Maric! 🙂

Thanks, Doc. Gosh, I hope to see you at a DSA meeting next year!

You’ll find sites for them on iNaturalist, Wendy!

Yes, there is something really compelling about those flowers. Thanks, Bliss!

Thanks, Margie. It means a lot coming from you.

Thanks so much, Gail. Yep, it is indeed a form of mindfulness.

Hi Bryan!

Thank you for this fascinating essay and for always bringing to light new stories about the wonders of nature. Coincidentally, I think I may have seen a species of Grass of Parnassus last week on a visit to Lake Willoughby, in a wet area alongside the road. There’s always so much more to know about nature!

Thanks for sharing this “manifestation of joy and wonder and mystery” with those of us unfamiliar with this perennial and It’s favorite bee. Do other types of bees come to it for pollen as well, I wonder. As the climate warms perhaps other flying insects will come north and find it not to the disadvantage I hope of that little bee.

Great essay Bryan! Really fascinating! And the flower is gorgeous…it is well-dressed in it’s pinstripes. Thanks for broadening my view of the nature that is all around us.

What a fascinating flower! Your photos of it are exquisite. I’d love to see it in the wild sometime. I assume it is found in a fen or bog?

Thanks, Bryan! You’ve opened my eyes to another beautiful and astounding part of nature!

Fabulous piece! I had no idea stamens could do such choreography. Gorgeous photo (no surprise).

Ahhhhh, when the”unruly pace of life” seems too much, along comes Bryan to the rescue. Thanks again for your lesson on peace and perserverance! I hope to see that tricky lovely flower some day! georgeann

Ah the joy of a singular focus in the natural world which drives out all other distractions!

Thank you Bryan for bringing the complexities of what, at first glance, would seem to be a simple but beautiful species of plant. Well done my friend.

Such an addition to my morning. thanks. Will be looking for these; maybe one day..

I happened on a small clump of these beside a mill stream in Shaftesbury VT a few years ago. They took my breath away… unexpected treasure, never seen before or since. Thanks for this juicy detail about its secret life.

Another great essay Bryan. Thanks for sharing your observations of nature’s cleverness in an awe-inspiring way!

Your observations and comments are indeed wonderful. Your solitary mindfulness in watching specific species is something to admire and follow. Thank you for all your incredible blog posts