Flowers and Light

New Evidence on the Evolution of Butterflies

Which is the greatest relationship in the history of the world? Nope, not Antony and Cleopatra. Not pencil and paper. Sorry, not Lennon and McCartney. Not even peanut butter and jelly.

It is instead the bond between insects and plants. Plants provide insects with food, shelter and defenses (chemical and physical). Insects offer plants nothing less than a future — the gift of pollination. Their shared evolution, millions of years in the making, has produced staggering diversity and beauty on Planet Earth.

I could go on at length about this relationship, but I have news for you about butterflies. It turns out that the bond between plants and insects, notably flowers and butterflies, is even stronger than we had long believed. So says an illuminating paper on the evolution of butterflies published this week in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

To fully appreciate this lasting relationship, you must first know this: butterflies are basically moths that learned to fly around during the daytime. According to the new research, moths first showed up on earth about 300 million years ago. With chewing mouth parts rather than a proboscis (even as adults), these early moths fed on primitive non-vascular plants (probably bryophytes). Butterflies branched off the moth lineage 200 million years later, as almost an afterthought in moth evolution. Of the 160,000 or so known Lepidoptera species on the planet, only about 19,000 of them, or 11 percent, are butterflies.

So what drove this evolution of butterflies? For a long time bats were prime suspects. Although various moth lineages developed the ability to hear or even jam bat echolocation, certain moths came up with another strategy: daytime flight. After all, by the light of day there were no bats. Life under the sun also caused these ambitious moths to evolve with ornate markings and bright colors — for mate recognition and defense against predators (mostly birds and bigger insects out there during the daylight). In other words, these day-flying moths became butterflies.

The research undermines the bat-butterfly hypothesis.

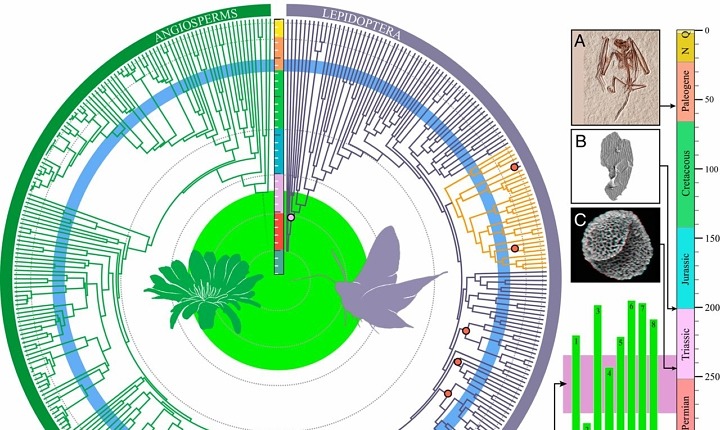

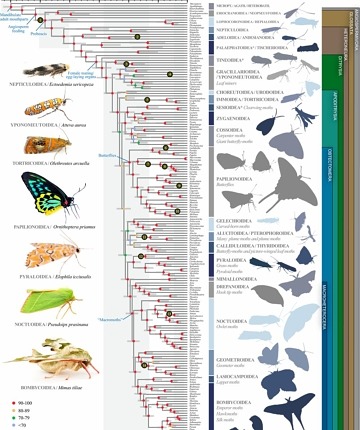

But the new research revises the timing of all this evolution in a way that undermines the bat-butterfly hypothesis. By examining the genetic code of 186 extant moth and butterfly species, the authors, a team of 20 biologists from around the world, pieced together an updated Lepidoptera phylogeny (those lovely diagrams below). It postulates that butterflies showed up on the scene about 98 million years ago. Bats didn’t arrive to the drama for another 50 million years.

More importantly, waiting there by the light of day 98 million years ago were angiosperms — the huge group of flowering, herbaceous plants. So began the great daytime bond between butterfly and flowers. Both groups flourished, especially those butterflies with colors, markings and other traits for avoiding daytime bird predation. The new timeline goes basically like this, reflected as well in those diagrams at the end of this post (dates are approximate):

- 300 million years ago (mya) — Primitive moths arrive on the scene. Lacking a proboscis, they have chewing mouth parts for eating plants.

- 241 mya — Moths develop a tube-like proboscis, which becomes a unifying step in Lepidoptera evolution and a big force behind rising Lepidoptera diversification.

- 125 mya — Bees join the party and help drive angiosperm evolution, notably diversity in flower form and color.

- 98 mya — The first butterflies branch off from moths, exploiting the nectar from the exploding plant diversity, the “great radiation” of angiosperms.

- 51 mya — Bats are latecomers, appearing some 47 million years after butterflies took to the skies (and to those flowers). By now, butterflies and plants are already getting along nicely.

There’s a lot more than meets the compound eye going on here (which is usually the case in nature, particularly among insects). It turns out that hearing organs originated in at least nine different nocturnal moth lineages, four of which appeared millions of years before echolocating bats. So those “moth ears” could have been a favorable trait for other reasons, most likely helping moths hear predators (and therefore survive in the struggle for existence). Once bats came along, the lineages that could also detect echolocation would go on to survive more readily at night (and diversify).

What I like most about this study is that it’s an affirmation of that great bond between insects and plants. Bats, too often maligned and misunderstood, most certainly have their rightful place in the world. But it’s nice to know that the force of evolution moving a certain group of moths from the darkness into the light didn’t necessarily include creatures of the night, but rather the seductions of flowers in the sunshine.

Publication Figures, Notes and Citation

For the circular diagram: The key things to note here is that the center of the diagram corresponds to ~350 million years ago and the outer diameter is today. The lepidopteran clade (or family tree), in blue branching, begins near the center at 300 mya at the close of the Carboniferous. Butterflies are represented by the yellowish clade (at about 2:30 if the diagram were a clock face), originating 98 mya; the rise of bats shows as the blue ring representing a zone of 65-55 mya. A kind of parallel radiation of angiosperms shows on the left half of the clock face in green.

For the next diagram: A lepidopteran family tree progressing, left to right, from 300 million years ago to present. Butterflies are marked at 98 mya. More detailed notes on each image are in the paper.

This open access article is distributed under Creative Commons Attribution-Non-Commercial-NoDerivatives License 4.0 (CC BY-NC-ND).

My banner images above: American Lady (Vanessa virginiensis) nectaring on a Rudbeckia species. © Bryan Pfeiffer

Citation

Phylogenomics reveals the evolutionary timing and pattern of butterflies and moths. Akito Y. Kawahara, David Plotkin, Marianne Espeland, Karen Meusemann, Emmanuel F. A. Toussaint, Alexander Donath, France Gimnich, Paul B. Frandsen, Andreas Zwick, Mario dos Reis, Jesse R. Barber, Ralph S. Peters, Shanlin Liu, Xin Zhou, Christoph Mayer, Lars Podsiadlowski, Caroline Storer, Jayne E. Yack, Bernhard Misof, Jesse W. Breinholt. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. Oct 2019, 201907847; DOI: 10.1073/pnas.1907847116.

Thanks so much for the note, Gail. Even though it might be overstated, I guess we can’t state it enough: it’s all connected out there. 🙂 Thanks, again!

I just want to say, as an amateur, one of the first things I realized was that to know the butterflies I had to know the plants. Not long after that, I realized that to know the plants I had to know the soil (a little harder). It all goes together. . .

I learned a lot from your wonderful article – thank you!

Yeah, go figure. But those odes will still eat those leps for lunch!

You’re most welcome, Louise. It’s an honor!

sooo…. 300 mya leps showed up…hmm. Isn’t that about when odes showed up? You can no longer brag about how old odes are my friend. haha.

Thanks, once again, Bryan for deepening our understanding of the incredible web that weaves this natural world together so exquisitely.

Louise

Bryan…Do these “white woolys” morph into anything???

Yes, you’re probably referring to Carol’s query. That was my assumption as well.

As you know, Kate, the plant and insect folks have much to appreciate and share together. I could write forever about it.

You’ve just made my day. Thanks, Vicki! 🙂

Thanks, Brian!

You’re welcome, Susan. (Hope the photography and writing are going well!)

Hi Carol,

Those are most likely Hickory Tussock Moths (Lophocampa caryae). Lots of them this fall. Careful — the can sometimes cause skin irritations if you pick them up. (Hard to resist.)

Thanks, Sally. See you when the odes fly!

Yes, please! 🙂

The flowers that let a thousand proboscises evolve! 🙂

Thanks, Bernie. I’m afraid we’re too late — just a passing fad to that long evolved history of plant and insect. They’ll certainly outlive us on Earth. 🙁

Is that the hickory scan worm moth?

Bryan, what a lovely condensation of that paper so we quickly got the gist of this big picture of “co-driving” evolution between vascular plants and diversifying insects . . . And later, the mammals, aka bats! Thanks!

Seeing a new post from you pop up in my inbox always makes me smile with anticipation. Thank you so much for your wonderful blogs.

Excellent read Bryan and love your shots as well.

Very interesting – thanks, Brian!

Bryan…. We seemed to have a lot of white “fluffy” caterpillars this year which I don’t recall seeing before…they had black antennae and are quite small… Thanks

Wonderful article and SO interesting. I enjoyed it immensely. Thanks for sharing.

Sally Edwards

Food or sex.

Absolutely fascinating, Bryan. I always considered flowers seductive – nice to know I’m not alone

Bryan, Thank You for taking us from chewing mouth parts to proboscis, from bees to angiosperm / flower color, from moths to butterflies and finally to bats – condensing a science paper and 250 million years of evolution while highlighting some of the magic of plant and insect relationships – in an informative post .

Now if we could just fast-pace the evolution of the relationship (bond) of man with insects and plants towards a complimentary and mutually beneficial strategic outcome.

Plant warm hugs and native plants. (Or at least plants that have developed relationships with with other organisms in our ecological environment).